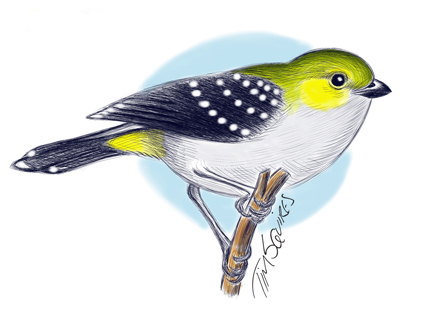

The population of the forty-spotted pardalote might be in freefall, seemingly headed to extinction, but the people of Bruny Island are not going to let the little bird die.

The population of the forty-spotted pardalote might be in freefall, seemingly headed to extinction, but the people of Bruny Island are not going to let the little bird die.

On a sunny afternoon in the Jetty Café at Dennes Point, Bruny Islanders were talking up the bird they describe as the “quiet achiever”, saying that it was too precious to their community to be allowed to go the way of the dodo.

Dennes Point is famous in forty-spot folklore as having the largest population of the pardalotes on private land and that 100ha property at Dennes Hill has set a benchmark for how landowners and conservationist can work together to save threatened species on not only Bruny but throughout Australia and probably worldwide.

The fight to save the forty-spot was outlined by conservationist Sally Bryant during the Bruny Island Bird Festival when she revealed a staggering decrease in forty-spot numbers over the past two decades.

Dr Bryant, of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy, said that numbers of this tiny endemic Tasmanian species had dropped by about 60 per cent in recent years, and its total population now stood at between 1200 and 1500 birds spread mainly across Bruny and Maria islands.

She conceded that we had all become “complacent” about the species’ conservation status, thinking that because much of its habitat was safe in reserves, it was secure in its numbers but alarm bells started ringing when birdwatchers and researchers failed to find forty-spotted pardalotes in areas where they had traditionally been more common. A detailed survey was conducted two years ago, that revealed the population collapse.

Dr Bryant said that the decline in forty-spot numbers was largely due to the long-term drought which over the past two decades had steadily caused die-back in the trees that the birds rely on for food and cavity nesting sites, the white gum (Eucalyptus viminalis). The forty-spots feed in the white gum canopy on insects and manna, the sugary substance exuded by the trees in response to insect attack.

Even in pre-European times, the total population of the highly-specialised forty-spotted pardalote was probably never large compared with other Tasmanian species. But with settlement and the clearing of white gum woodlands other more aggressive bird species had been able to expand their range and put its numbers in a precarious position.

However, Dr Bryant, former manager of the threatened species section of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, and an authority on the species, is far from pessimistic about the forty-spots’ fate.

She said that Bruny Islanders had long embraced this species and that one pioneer family, 89-year-old Josephine Denne and her late husband Ross, had chosen not to sub-divide part of their working farm but donate the land as a nature reserve for the bird’s long-term protection. Jo and Ross never wanted Dennes Hill to be cleared or lost to subdivision and had always managed it carefully using a mix of light fire and grazing.

Other landowners were also responding to the forty-spot challenge by preserving and planting white gums to create wildlife corridors across parts of Bruny’s south and north islands and new data on climate change predictions meant that white gum were being planted in wetter areas that would support their growth in future years.

Among these landowners are the Wardlaw family who were finalists in this year’s National Landcare awards in recognition of the outstanding way they are managing their Waterview Sanctuary property for conservation and sheep production, and the Indigenous Land Corporation which has won praise for the management of its Murrayfield property.

“Bruny Islanders are not going to let this bird die. They have taken it to their hearts,” Dr Bryant said during her bird festival talk, attended by both visiting birdwatchers and local residents.

In the Jetty Café, a letter pinned to the notice board spoke as elegantly about the pardalote as Dr Bryant’s words.

Visiting birdwatchers fromNew South Waleshad written to thank staff for pointing out where the 40-spots could be found. The couple had even managed to photograph the bird, and enclosed a picture for the staff to see.

They said they had told their birdwatching group about Bruny, its special species and its special people.

“They all want to visit,” they added.