A bird of the beach, the white-fronted chat, scurried through the long grass surrounding the house that is home to the Bruny Island Men’s Shed.

A bird of the beach, the white-fronted chat, scurried through the long grass surrounding the house that is home to the Bruny Island Men’s Shed.

A chilly wind was blowing in off the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, whipping white horses on the grey seas. A wisp of smoke rising from the shed’s chimney, and a steaming kettle on a bench misting the windows of the house’s kitchen told me it was the place to be on a rainy autumnal day.

I ignored the chats, and a gannet bobbing up and down on the ocean, for the wood-fired warmth inside the shed.

Having always struggled to get to grips with woodwork and machinery, I’m not much a handyman and so the shed presented itself as a foreign environment for me. I just hoped once inside the conversation would not turn to dove-tail joints and sprockets.

I was entering the shed for other reasons, however: to witness a remarkable partnership between men used to working inside with their hands and dedicated scientists working in the great outdoors on conservation.

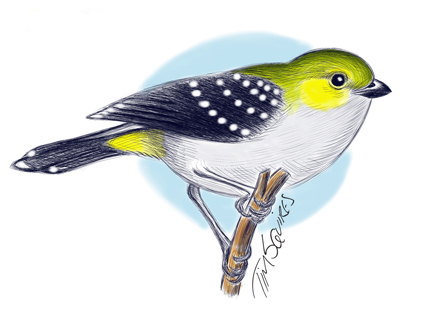

BrunyIsland is not only home to birds of the beach and ocean, like the chat and the gannet, but is also the main breeding ground of one of the world’s rarest forest birds, the forty-spotted pardalote.

The men of the shed had embraced a conservation programme to provide the tiny pardalotes with nesting boxes and I had been invited over to Bruny to attend a ceremonial handing over of the boxes to the researcher heading the project, Amanda Edworthy.

In all 200 boxes, painted khaki and with bold white numbers on them, were stacked high in the shed ready for Ms Edworthy to put them in position throughout Bruny’s north and south islands ready for the pardalote breeding season later in the year.

In all, the shed members have spent 136 man hours constructing the boxes after receiving the order from Ms Edworthy, a PhD student at the AustralianNationalUniversity, at the start of the year.

The basic design and dimensions of the boxes were drawn up by Ms Edworthy but the men came up with a couple of prototypes which enabled the researcher to improve on her design.

A campaign to finance such a large number of boxes had been run by the Bruny Island Environment Network (BIEN), which has sought $25 for each box to cover the cost of materials and paint.

BIEN’s secretary, Marg Graham, said the entire project was a good example of members of a community working together to make a difference when it came to the environment.

Each sponsor of the boxes could stipulate where their own numbered box was placed as long as they were within a spread of white gums, the tree favoured by the forty–spotted pardalotes for feeding and nesting.

The endemic forty-spot – one of Australia’s smallest birds at only nine centimetres in length – is only found a handful of places in Tasmania, BrunyIsland having the biggest population.

Numbers of forty-spotted pardalotes have been in freefall in recent years, dropping by about 60 per cent, and the total population now stands at between 1200 and 1500 birds.

A lack of nesting hollows in white gums – trees suffering dieback in recent years because of drought – had been thought previously to be the main reason for the pardalote population collapse but Ms Edworthy is already discovering other problems facing the birds, including mortality among chicks caused by parasites infesting nests.

The provision of the nest boxes will allow Ms Edworthy to study this threat more closely and at the same time the boxes will reduce pressure on existing tree-cavity nesting holes.

After the handing-over ceremony – involving tea and a rather nice cake that one of the shed member’s wives had baked – there was work to be done on a final batch of 40 boxes. As the sawing and hammering started, I felt it an appropriate time to leave.