LIKE the seasons, a human life comes full circle. The seasons have a symmetry and I’ve found that life too often follows a pattern, events and experiences that had gone before are apt to return, even if in a slightly different form shaped by the passing years.

LIKE the seasons, a human life comes full circle. The seasons have a symmetry and I’ve found that life too often follows a pattern, events and experiences that had gone before are apt to return, even if in a slightly different form shaped by the passing years.

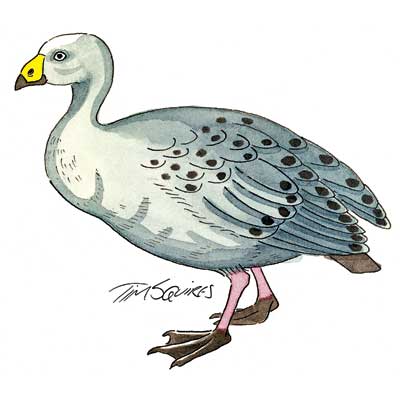

On a rainy and windswept morning when commonsense should have found me at home I came across a lone Cape Barren goose at the Waterworks Reserve and immediately I was transported back to memories of my childhood and seeing this curious bird – clothed in grey plumage with a patch of puce-green skin, or cere, on its beak – behind wire in the duck enclosure at the London Zoo.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing at first when the Cape Barren goose came into view at the Waterworks Reserve. The species is still considered one of the world’s rarest geese, although in recent years populations have built up to such numbers that they are secure. All the same, it’s not a bird you would expect to find in the suburbs of Hobart.

The sighting was a long way from the time when I first made the Cape Barren goose’s acquaintance as a schoolboy in the 1950s at the London Zoo. Then the goose was in danger of extinction and captive breeding populations had been established in zoos around the world as an insurance policy in case the birds vanished from the wild.

I can remember to this day reading the sign on the goose’s cage saying that these birds came from a far-flung place called Tasmania, and birds born in the London Zoo might one day have to be flown back to Australia. These strange geese looked so different from the wild geese I was used to seeing in Britain, which were generally grey-brown in colour, with pink bills. I distinctly remember noting that the Tasmanian geese not only had most ungoose-like plain grey plumage but red legs and black feet. It was as though someone had stitched it together from various exotic bird parts, a bit like the duck-billed platypus which, when specimens first arrived in Britain, scientists at first refused to believe that such a creature existed. They thought the specimens were a hoax, a bird-beak fashioned onto the body of some kind of mammal.

I learned from studying this strange goose that it had another quality that separated it from other geese. It had an ability to drink salt or brackish water which allowed the geese to remain on offshore islands all year round, and breed there.

This mechanism might have allowed the geese to survive in remote places for millennia but they had no defence when whalers and sealers colonised the goose stronghold of the Bass Strait islands, including Cape Barren Island from where they derive their name. The geese made an ideal food source.

By the 1950s, numbers of the Cape Barren goose were so low that conservationists feared they may be close to extinction. Various initiatives were quickly taken, including introducing captive-bred birds to Maria Island on the east coast and banning hunting in their last redoubts, and the goose population slowly staged a recovery to the point where they are no longer considered to be in danger.

The goose at the Waterworks stayed all summer and each time I saw it I felt that same tinge of schoolboy excitement I had had when I visited the London Zoo all those years back. Did the sight of the Cape Barren goose in London, and the other Australian birds and animals in the zoo, lead me in thought and then deed to a new life in Australia years later?

Certainly the little boy in short pants, clutching the cheese and tomato sandwiches his mother had made for him, would never have believed at the time he would one day be seeing these geese in the wild in Tasmania, not too far from his home.