FOR some months now the wall of my study has been adorned by a print of a rare colonial picture which provides a glimpse of how Hobart and its surroundings looked during the first days of settlement.

It’s an idyllic scene and I go there when the rain is falling beyond my study’s window and I can’t experience the real thing.

The long-forgotten painting by John Charles Allcot, recording a tranquil and leafy Sullivans Cove at Hobart’s foundation in 1804, was brought to public attention by the Sunday Tasmanian last year after it was discovered in a Sydney library.

The newspaper published the picture in full colour across two pages and I felt compelled to frame it and place it above my desk. It is truly a magnificent work of art but beyond the skill of the artist, and the beauty of Hobart as first seen by Europeans, it gives us an indication of just how the landscape has been transformed by man in 200 years, and how much of our natural heritage has been lost.

In the picture, Lieutenant Governor David Collins’ two ships, the Lady Nelson and the Ocean, are at anchor just off the coast where the stream we now know as the Hobart Rivulet enters the Derwent. Stringybarks hug the coastline, and just behind them what look like towering blue gums form a dense canopy of foliage that spreads away to the lower slopes of Mt Wellington.

As with the same location today – the view in the picture is from the island that became Hunter St in the modern Hobart rising in part from reclaimed land – the mountain towers over the vista, its Organ Pipes bathed in sun.

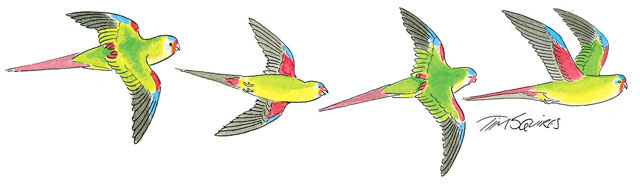

Looking at the scene in 1804, you can almost feel the gentle, warm breeze rustling the gum leaves, and hear the swift parrots calling out as they cross the canopy in rapid flight.

The descending, thin song of the scarlet robin would have risen from the flowering yellow banksias as the yellow-tailed black cockatoos prised open cavities in 200-year-old trees to build their nests, showering the British military men erecting tents below in shards of bark.

And at night, these same soldiers in a strange, if not forbidding land, would have carefully hidden and stored their boots, to save the leather from being chewed by marauding Tasmanian devils, and the haunting call of the boobok owl would have sent them to sleep under the canvas. Another night-time experience, no doubt, would have been the sight of Tasmanian tigers, prowling the dry woodlands where stringybark and golden wattle give way to blue gum.

Since those early days 50 per cent of blue gum forest has vanished from Tasmania, along with the birds and animals that live in them. Among these is the swift parrot, whose main food source in summer is the pollen and nectar from blue gum blooms. It once flew in its hundreds of thousands but is now down to a fraction of its previous number and giving concern for its chances of survival.

The Tasmanian devil has not only vanished from southern areas of Tasmania, but is battling its own fight for survival, the victim of the mysterious facial tumour disease.

The yellow-tailed black cockatoos, although not threatened as yet, still struggle to find suitable nesting sites, seeking out trees that must be at least 100 years old to provide the right-sized cavities. The same applies to another big, cavity-nesting species that is on the threatened list, the masked owl.

All is not doom and gloom, however. The importance of the urban environment has been increasingly recognised in recent years, with the various bushcare groups around the city doing great work in restoring native habitat, mainly in controlling invasive weeds and replacing them with native plants.

And there are efforts being made to replant trees that have been lost, the coastal white gums among them that provide a specialist and highly restricted environment for another endangered, Tasmanian bird far more common in earlier times, the forty-spotted pardalote.

Much may have been lost since European settlement – as the Allport landscape which was lost to public viewing for so long a period demonstrates – but we are lucky that so much remains to be saved for future generations 200 years hence.