Black cockatoos – their mournful cry carrying far and wide – intruded on a day which should have been free of birds, one devoted to another favourite subject of mine, Victorian history.

I was in the middle of a tourist presentation called Louisa’s Walk, a stroll intoTasmania’s convict past that embraces the Cascades Gardens in South Hobart and the nearby site of the Cascade Women’s Factory, when the yellow-tailed black cockatoos paid our party a call.

The life of Irish convict Louisa is recreated by a group of actors in an award-winning historical experience and I must say I was so engrossed in Louisa’s true story that my interest in wildlife was in some kind of suspended state in my consciousness, as was place and time. It wasn’t June 7, 2012, but 1840, and I was standing in the public gallery of the court in London watching Louisa being sentenced for the heinous crime of stealing a loaf of bread to feed her family, a family that had newly arrived in the British capital to escape poverty inIreland.

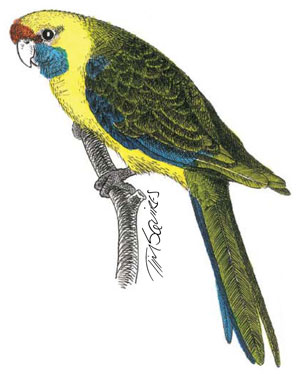

Birds soon brought me back to the present, however. First it was Tasmanian currawongs flying from the direction of Mt Wellington followed by forest ravens, green rosellas and then the yellow-tailed black cockatoos but, far from distracting me, they strangely added to the performance as “extras”.

By coincidence Judith Cornish, who runs the Louisa’s Walk tours along with her husband, Chris, had mentioned birds when I had first decided to take the tour and sought more details about it.

Cornish had said in passing that superb fairy-wrens were often to be seen in the grounds of the female prison during performances and on one memorable occasion a scarlet robin had perched on her head when she, too, was in full flight “in character” as Louisa.

The robin had as big a shock as the audience to find where it had landed, before fluttering to the high wall of the prison to watch the rest of the performance from there.

The story of Louisa was one of unfathomable misery and cruelty as her fellow, modern-day travellers took the journey with her from London, on the convict ship Rajah, to the horror of life in the prison factory and then abuse at the hands of the man who had secured her services as a servant.

And all the while birds crossed the skies, calling as they went, drawing irresistible metaphors about freedom from incarceration and chains.

The women in the prison complex – at some times more than 1000 of them – would not have had to chance to see the birds, even draw and carve them as some of the male prisoners at Port Arthur had done to give them a distraction from the reality of their lives. The high walls of the women’s prison and accommodation blocks suspended above the ground floor blotted out any view of birds, as it did Mt Wellington. The prison in fact was described as “in the shadow of death” by women having to return to it.

The cries and songs of birds, though, would have penetrated the standstone walls and the women no doubt would have heard them.

As I studied a washing tub, the soft sandstone on one side worn away by years of human toil, I heard the black cockies and looked up to see them passing the factory with slow, lazy flaps of the wings.

Their cry has been described as a lament but Louisa would no doubt have used another word for it derived from Gaelic – a keen. And she might even have used the Gaelic word itself, a caoine, for her own lament for a life lost.