We all have our harbingers of spring. To the farmers it’s the welcome swallow that tells them when to sow, and then when to reap at the end of summer.

We all have our harbingers of spring. To the farmers it’s the welcome swallow that tells them when to sow, and then when to reap at the end of summer.

To the orchardists it is the arrival of the black-faced cuckoo-shrike that signals not only blossom on apple and pear trees in spring, but picking time when the summer birds – as they are known in country districts – retreat to the mainland during the autumn.

To me it’s not the actual arrival of spring that is heralded by the birds and their songs but the expectation that there is light at the end of the tunnel, there will be an end to the winter on its coldest, and darkest days.

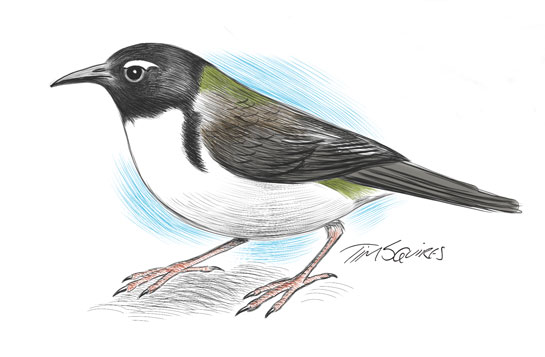

Although birds tend to curb their singing in winter – or at least not break into the full, robust songs of spring and early summer – there is one species guaranteed to bring the warmth of music to the bleakest of days. So it was on June 21 this year, the winter solstice, when a joyful party of black-headed honeyeaters in my garden defied the reality that not only were the skies overcast and grey and frost lingered on the lawns at mid-morning but it was the shortest day of the year, with sunset at 4.43pm.

The birds had come like carol-singers knocking on doors in ancient times when snow lay thick on the cobbled streets. Their cheerful calls lifted the spirits.

I heard the singing from inside my home where I sat by a log fire, and went out onto my deck to look.

The song is a series of chimes, formed into a pleasant loud chatter that emanates from the tree canopy, where black-headed honeyeaters go in search of invertebrates hidden in buds and under bark.

It is worth hunting out the black-headed honeyeaters high in the treetops because they are beautiful little birds. Along with the closely related, but scarcer strong-billed honeyeater they are only found in Tasmania and form a branch of the honeyeater family that has largely eschewed feeding on nectar and honey, to feed on insects instead, although they still retain the brush-tip tongues to take food from flowers, if necessary.

A paradox of nature is that on the shortest day of the year – especially if the sun is shining – birds will often break into the songs expected of them at the height of summer, when days are longest and hottest. A biologist friend has a theory that the birds confuse the shortest day with the longest, the solstice event triggering a response in the birds that they cannot control.

I feel that same surge of optimism and enthusiasm when I contemplate the change of seasons, especially the coming of spring, as I think we all do. It informs us that we are all influenced in some way to the rhythm of the seasons.

Winter for birds still represents a struggle for survival, when food is in short supply. How such fragile creatures survive is as remarkable to me as the wonder of flight, and in turn the wonder of migration when birds make epic journeys. It’s all about reading the weather, reading the seasons, knowing that spring is just around the corner if the trials of winter, the trials of life can be ridden for a month or two, like the winds.

A singing, happy party of black-headed honeyeaters still have much to teach us as the first daffodil stalks thrust through the leaf-litter in our gardens, and the first flush of flowers show in the canopy of silver wattles. What mysteries birds hide within their frail bodies, what lessons they hold as we strive to control the seasons, to shape them, to make our own lives more predictable and certain.