OUR connection with the birds all around us can be found in the strangest of places but none as strange as the workings of a mechanical excavator.

I had a curious bird-watching experience at the end of winter when contractors arrived to shore up the elevated dirt drive of my home, which after heavy rains had begun to subside into my garden.

I watched in fascination all morning at the skill of the excavator operator as he dug a trench in the narrow confines of our drive, and piled up tonnes of earth to be shipped away by truck. I was not the only one to stand in awe of the excavator and the driver’s skill. The activity attracted kids from the neighbourhood who arrived as if from nowhere to have a look.

And then something remarkable happened. Amid all the noise, the thumping and crashing and whirr of caterpillar-tracked wheels, a family of superb fairy-wrens flew in, attracted by all the commotion, keen to have a look for themselves.

It soon became clear, however, the fairy-wrens were not merely interested in watching the excavator, as with us gawking humans standing around. They viewed this mechanical monster as a meal ticket.

The excavator in disturbing tonnes of wet earth had in turn disturbed and uncovered invertebrates buried in the soil. For the fairy-wrens it provided a handy meal on a freezing winter’s day – the coldest of the year – which had laid a coat of frost over my garden and frozen the top layers of soil, the usual hunting ground of the wrens. I watched the fairy-wrens for an hour and then another bird arrived, a blackbird, to share in the bounty.

When the excavator driver took a lunch break we got to talking not just about the job in hand, but about the fairy-wrens who had joined him.

“Oh, it’s so lovely to have their company on the job,” he said, “but it’s not unusual. I sort of look for them when I’m working, hope they will arrive.”

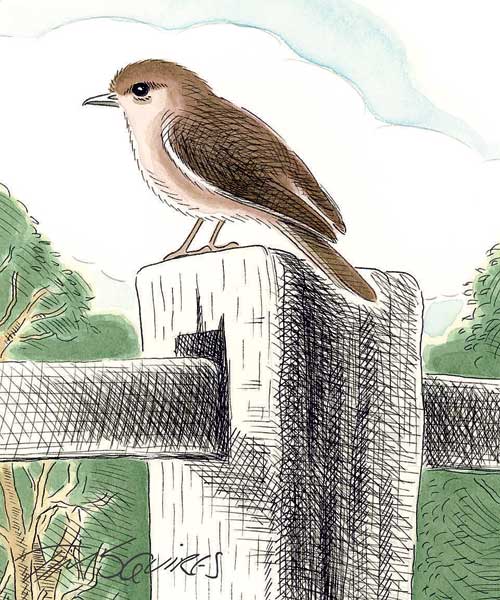

He listed other birds attracted, perversely, to the workings his digger. These sometimes included scarlet robins that often perched on fence posts in country districts, and on fences in the more leafy suburbs, as he went about his noisy, disruptive business with his excavator and bulldozer.

“Now I love the fairy-wrens but I gotta say the robins have to be my favourite, with those fiery, crimson breasts.”

Birds traditionally have been attracted by the activity of man, especially on farms. It is the gull and crow that follow the plough – as many an English poet has noted – and in summer welcome swallows and tree martins can often be found in association with farmers moving cattle and sheep about paddocks. This activity disturbs flying insects. The same applies to the dusky woodswallows we also see in summer, although these are not related to the true swallows and are members of the magpie and currawong clan.

Much folklore is attached to the association between birds and farmers in Europe but there are also references to it in the more modern folklore of Tasmania.

It was noted by the early settlers that a relative of the scarlet robin – the dusky robin which is only found in Tasmania– would arrive when land was being cleared to create field and paddock. The dusky robins had a habit of perching on the stumps of trees that had been cut down and a local name for them – the stump bird or stump robin – can still be heard in country districts.