The rising sun had painted the sky in hues of pinks and blues, and I was walking a beach thinking of another time, if not another place.

The rising sun had painted the sky in hues of pinks and blues, and I was walking a beach thinking of another time, if not another place.

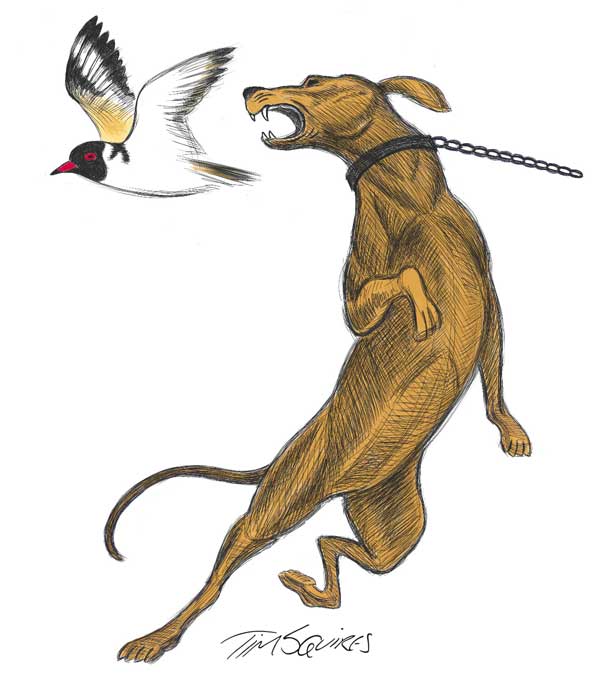

It was the year of 1832, and a fearsome dog called Jowler was tugging at its chains, trying to chase a hooded plover straying a little too close to its kennel.

My thoughts had wandered like my footprints in the wet sand at Eaglehawk Neck’s sweeping beach, where I had gone in search of Tasmania’s convict history, putting birdwatching on the back-burner for a change.

I’ve long been long fascinated by the dog line that once spread across the isthmus at Eaglehawk Neck and wanted to take a close look at the site where 18 hounds were in place to prevent convicts who had managed to slip their own chains at Port Arthur reaching Hobart. The spot is now marked by a sculpture of a canine – cast in bronze and standing big and bold – that is a memorial to the dog line and the hounds that manned it.

I had set out to explore the whole area, which includes surviving military buildings, but I had not been prepared for a discovery of a different kind – a family of endangered hooded plovers. And that’s when my imagination took flight to the past. The hooded plovers had been a witness to history in the making, the brutality of the dog line which in turn was a sub-plot to the wider cruelty of transportation and incarceration in hostile and alien lands.

The plovers – or at least their ancestors – would have known not just Jowler but Achilles, Pompey, Ajax, Ugly Mug, Tear’em and the other barking, howling hounds which at one time or another were chained across the isthmus. The dog line extended down to the ocean itself on both sides of the spit, where floating platforms were placed with dogs aboard in case the convicts tried to wade and swim their way to freedom.

Describing the dogs in 1837, Harden S. Melville wrote: “There were the black, the white, the brindle, they grey and the grisly, the rough and smooth, the crop-eared and lop-eared, the gaunt and the grim. Every four-footed black-fanged individual among them would have taken first prize in his own class for ugliness and ferocity at any show.”

Although the dogs were ferocious, the hooded plovers and the other shorebirds like pied oystercatchers had no need to fear the dog-line hounds. The dogs were chained after all and would never give chase and stray into breeding areas.

It is a far cry from the crowded beaches of not just Eaglehawk Neck but other coastal areas of Tasmania today where human activity, including dog walking and horse riding, is pushing the hooded plover towards extinction.

The immediate beach that is the site of the dog lines would no doubt have been home to three or four families of hooded plovers in the days of the convict settlement, where today I was pleased to find a single family of three birds. On many beaches which should be prime hooded plover habitat with sand dunes and coastal plants behind a wide sweep of sand I often do not see a single bird.

I avoided the hooded plovers on my return to the hotel, walking along the road instead so they would not be disturbed as they fed. And passing the dog statue, I heard the soft warble of a scarlet robin, and turned to see a fine male perched on the replica bronze lamp suspended above the dog’s kennel.

Clearly the robin had also been a not-so-silent witness to history.