The patch of yellow grass in a shorn hay meadow held a secret within in its sun-burnt stalks swaying in the hot summer wind.

The patch of yellow grass in a shorn hay meadow held a secret within in its sun-burnt stalks swaying in the hot summer wind.

The secret was partially revealed as I approached the grassy oasis because overhead a bird of prey appeared as if from nowhere, letting out a shrill cry that echoed through the surrounding hills.

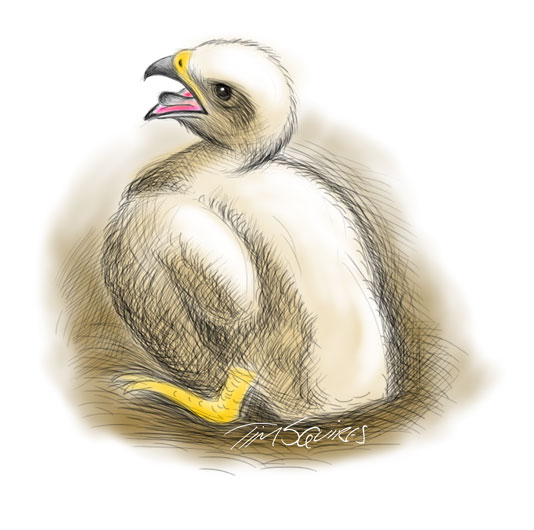

Treading carefully through the tall grass I suddenly caught sight of two creamy-white, downy shapes, perfectly camouflaged to hide in the grass. Then an open yellow mouth shaped in the form of a sharp, hooked beak.

I was looking at the nest of a pair of swamp harriers who had chosen the extensive property of Ross and Robyn Stanton at Cambridge as their summer home. Ross Stanton had wanted to show me the nest and young before they had taken to the wing for their first flight, in preparation for a longer one across Bass Strait to the mainland at the end of summer.

Ross discovered the nest by chance a few weeks previously while inspecting a paddock of long grass which was about to be cut for hay. He wanted to ensure that no weeds would contaminate the hay and had set out to mark areas where weeds proliferated.

After seeing a female swamp harrier take flight and discovering a nest with three eggs, Ross found himself marking not just a clump of dock weed but an area holding the nest.

Ross had previously discovered swamp harriers attempting to nest on his property, and again had left a patch of uncut grass around the nest site. The area had not been large enough, however, to totally disguise the nest and forest ravens had moved in to steal the eggs.

This time Ross was determined to give the harriers a fighting chance and, after marking the area of the nest with three sticks, ensured that the area to be left was a good four or five metres beyond the boundaries of the sticks.

His initiative was successful with the swamp harriers managing to rear two chicks which, with a steady food of wildlife from his property and surrounding areas, were soon developing into robust nestlings. The third egg failed to hatch.

Swamp harriers are Tasmania’s only migrating bird of prey, and they arrive at the start of spring so they can make of a meal of the young of an early nester, the masked lapwing, or plover as they are known in Tasmania. The harrier is easily identified because it prefers to fly close to the ground – quartering swamp, paddock and field in its hunt for small birds or animals – and has a distinctive white rump which can be seen even at a distance.

The swamp harrier’s preference for nesting on the ground puts their young at severe risk of being minced by mowers when hay or cereal crops are cut.

Countless swamp harriers are killed each year in this way and farmers are urged at the start of spring to check their properties for swamp harriers, and then to determine if they might be nesting. As Ross Stanton has proven, ensuring the harrier’s survival can be a simple matter of avoiding nest sites. In a big paddock, the area would be insignificant in relation to the crop to be harvested and there would be a bonus for the farmers – swamp harriers, after the plover nesting season is over, turn their attention to feral pests like pests and mice.

There’s another bonus, as the Stantons have discovered. From the front room of their home on a hill that has panoramic views over the Tasman Peninsula they are also treated to the majestic sight of one of nature’s great fliers; gliding, diving and swooping across their paddocks.