The chatter of birds, optimistic and cheerful at the end of winter, carried across the saltmarsh but all the same there was a sense of melancholy and loss in the spring air.

The chatter of birds, optimistic and cheerful at the end of winter, carried across the saltmarsh but all the same there was a sense of melancholy and loss in the spring air.

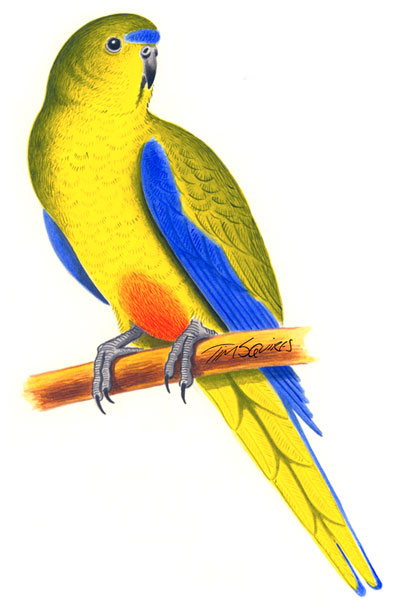

Amid the cacophony of birdsong, of melody in the marshes, piping from the rockpools, a once-familiar sound was missing – the buzzing of the orange-bellied parrot.

The Borrow Pit amid the Werribee wetlands in Victoria is noted for sightings of orange-bellied parrots but this September the tiny but beautiful birds have failed to show. It was the same along the rest of their migration route, stretching from the Coorong in South Australia to eastern Victoria. Only one orange-bellied parrot was seen in the whole area on its spring migration to its breeding grounds in Tasmania.

In all, only 10 parrots had been previously sighted all winter long raising concerns that, as predicted and feared, the wild population of parrots might be finally on the way out.

With only an estimated 35 parrots left in the wild I knew when I signed up for one of the regular mainland orange-bellied parrot surveys the chances of finding any of the birds would be slim. I was thinking odds infinitely greater than the proverbial needle in the haystack. I went anyway.

The bird-watcher always travels optimistically and my email correspondence with the survey’s organisers indicated that they thought the presence of a birder from Tasmania might bring them some luck.

It certainly looked that way when I arrived at the Werribee marshlands. Storms and high winds that had rocked and tossed the Spirit of Tasmania on the voyage from Devonport to Melbourne had subsided, the sun was out and the morning air crisp and new.

The Werribee refuge within Melbourne Water’s Western Treatment Plant comprises myriad lakes, ponds and lagoons of which the Borrow Pit is part. When I arrived the rasping song of the Australian reed-warbler rang out from the reedbeds behind me. Among rocks in the Borrow Pit shallows red-necked stints had arrived from their breeding grounds in Asia.

The population of orange-bellied parrots has been in freefall in recent years, despite a concerted campaign launched in 2006 to stem its decline. Then the Australian Government committed $3.2 million to protect and expand both breeding and winter habitat. The plan built on recommendations of the Orange-bellied Parrot Recovery Plan two decades earlier which brought together both federal and state governments, along with interested non-government organisations like BirdLife Australia.

With so few orange-bellied parrots left, scientists are now considering a plan to catch the surviving wild birds in their breeding ground around Melaleuca in far south-west Tasmania to boost a captive-breeding population currently being reared at a Parks and Wildlife establishment in Tasmania and in zoos on the mainland. This captive population requires an urgent injection of genetic diversity from the wild birds.

On a sunny spring morning in Werribee no one was talking of captive-breeding. A team of about 20 birders marshalled by the threatened bird network of BirdLife Australia was speaking of wild birds waiting to be found. The team split into five groups to head to areas of the extensive reserve where orange-bellied parrots were likely to turn up, mainly among the saltbush fronting Port Phillip Bay.

Two times previously in the winter the teams had gathered, in April as the birds arrived from Tasmania and then in July when they were settled in their breeding range.

I was told the best chance of finding the parrots was possibly to flush them from the saltmarsh, and their distinctive buzzing alarm call would set them apart from the closely-related blue-winged parrot even if only a brief glimpse was offered of them.

On a swamp in Victoria, meanwhile, the spring-time sympathy of birds remained without a vital player. The alarm call that for eons had alerted all the other inhabitants of saltbush and lagoon to danger was silent. And the sandpipers and stints were missing a fellow traveller, the resident stilts and avocets a winter friend.