In the fastest growing area of Tasmania, a battle for vital real estate was talking place right before my eyes.

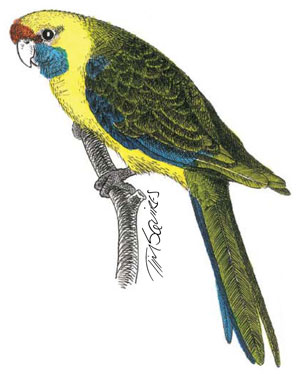

A green rosella was struggling desperately to ward off a pair of rainbow lorikeets trying to lay claim to its home.

The tussle took place in the Peter Murrell Nature Reserve on the outskirts of Kingston, in a Kingborough municipality identified as the fastest developing in the state. Land for homes in the area is at a premium. The same goes for nesting sites for birds.

What made the Peter Murrell confrontation all the more heart-rending was that the rainbow lorikeets had no place in Kingston, or indeed Tasmania. They are not native to Tasmania and their requirement for nesting cavities is placing an intolerable burden on the local species that also rely on holes in trees to rear young.

I watched the fight for a good half an hour, and am delighted to report that the green rosella finally won the day.

I was told my local birders that the tree in which the cavity is located has been a well-known breeding site for green rosellas for many years. The lorikeets would have to find a site somewhere else, probably stealing it from another pair of green rosellas or, worst, an endangered swift parrot.

The rainbow lorikeets have become a big problem in the area since first appearing there a few years back. It is believed a rapidly growing population has emerged from caged birds released from aviaries in Kingston and they are now on the verge of exploding out of control. Rainbow lorikeets are endemic to south-eastern mainland Australia and in the past have never been recorded in Tasmania, except for possible strays from the mainland sighted in the north of the state.

The invasion of Tasmania follows a similar trend in the rainbow lorikeet’s own homeland, with cities like Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane being over-run by them simply because they are one of the few species of bird that has managed to exploit man’s world. They happily make their home in city and suburb where they feed year–round on exotic introduced plants and enjoy being fed by householders who revel in their beauty.

I was very impressed, too, when I first saw them – arriving in Australiato live in Townsville – but I have since learned that this a rainbow somewhat tarnished at the edges. The rainbow lorikeets have become so dominant and numerous that they are squeezing out other birds, reducing the diversity of species in not only suburban areas but out in the bush.

The mainland cities – and to a certain degree those in Tasmania – have become the preserve of just a few common species: kookaburras, currawongs, rainbow lorikeets, noisy miners, little wattlebirds and introduced starlings among them.

The lorikeet-rosella confrontation could have been a metaphor for the history of the Peter Murrell refuge itself. The bushland comprising the reserve was once ear-marked for housing development before a campaign by local residents convinced authorities of its worth for wildlife.

Not only is it home to the endangered forty-spotted pardalote but provides a vital wildlife corridor – a green lung – between the rapidly spreading suburbs of Kingston and Margate to the south.