A little bird singing robustly in a park in London had something in common with a species singing just as loudly on the other side of the world, in Tasmania.

A little bird singing robustly in a park in London had something in common with a species singing just as loudly on the other side of the world, in Tasmania.

Both birds had modified their songs so they could be heard above the roar of the traffic.

As I wandered parkland surrounding the Royal Naval College in Greenwich last year, I was halted in my tracks by the beautiful bell-like song of the great tit. The bird might have been perched in an elm overlooking a busy bus stop but the roar of the Number 188 bus to Waterloo could not drown out its chimes.

I didn’t need binoculars to identify the bird singing. By coincidence I had heard both a recording of the song and seen a picture of the great tit months previously, during a lecture in Tasmania on how urban birds were moderating their songs to cope with the competing noise of the city.

The great tit, from studies in Scandinavian and British cities, is held up as the best example of this change in behaviour but researchers have also been looking for similar traits in Australian birds that coexist with people in the cities.

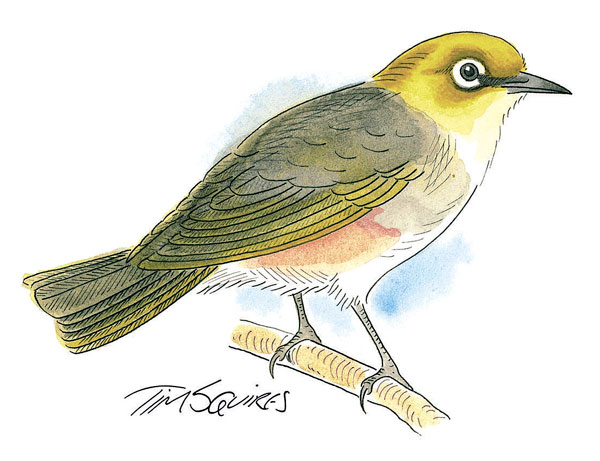

One bird that stands out here is the silvereye, which in recent years has been found to be changing its song to cope with the stresses of urban life.

It was initially believed that birds merely sang louder to overcome competing noise but further study revealed that the pitch and tone of the songs was all important. The songs were so different that scientists began to believe that perhaps birds were programmed through the evolutionary process to sing such new songs instead of learning them from their parents. The ability to sing in a certain way is an inherited trait in birds, but actual songs have to be learned.

The urban song is moderated, to give the songs a harder edge to overcome increasingly loud background noise created by human activity, which ranges from cars on suburban streets to planes flying overhead, to say nothing of the other familiar sounds of the suburbs in Australia, the whine and whirr of lawnmowers, whipper-snippers and chainsaws.

Birdsong can be divided into two types of sound. The more complex songs are used to declare territorial possession and to attract mates. Together with often intricate and melodious songs, birds also have truncated songs, or calls, to keep in touch with each other while in the treetops or on the wing, and to keep in touch with young. Calls are also used to warn of danger.

The silvereye, found commonly across south-eastern Australia, has been a good subject for research because it occurs in both urban and rural environments, its acoustic behavior has been well documented, and scientists have good knowledge of its genetics.

The lecture on urban bird song had only touched briefly on the great tit, as an example of what was being done in Europe regarding urban bird research. It was the silvereye that was the focus of the scientist outlining her work, Dominique Potion, from the Universityof Melbourne.

She had travelled to Tasmania as part of her studies at various locations around Australia, capturing silvereyes for morphological and genetic analysis, releasing them, and recording the songs of individuals in that population.

Were these new songs passed down through the genes, and not learned after birth? The research proved the latter – urban silvereyes, at least, will revert to a softer, more mellow song once they leave the urban jungles of the cities and head back to the countryside.