The arc of a rainbow spread across the Southern Ocean as a family of hooded plovers scurried across the sand.

The arc of a rainbow spread across the Southern Ocean as a family of hooded plovers scurried across the sand.

The wind blew fierce and strong off CloudyBay at the tip of south BrunyIsland but the plovers were not to be deterred from their seashore business.

It was good to find them on the beach on this autumnal day washed with rain, sun and rainbows.

The hooded plover has vanished from many of the beaches of south-eastern Australia where it was once common. On BrunyIsland, however, the tiny shorebird is holding its own.

The sighting of the “hoodies” was especially pleasing for Megan Cullen, the conservation officer for beach nesting birds with BirdLife Australia who was leading a walk for Bruny Islanders concerned about the future of the hooded plover and other beach nesting birds.

Ms Cullen had been invited from Melbourne by the Bruny Island Environment Network to explain how members could “make a difference” to ensure that shorebirds had a safe haven on the twin islands.

During her presentation in the community hall at Lunawanna, Ms Cullen explained that throughout its range the plover was under threat, mainly because it chose beaches for nesting sites that also proved an irresistible lure for humans, especially in the summer months when plover breeding activity was at its height.

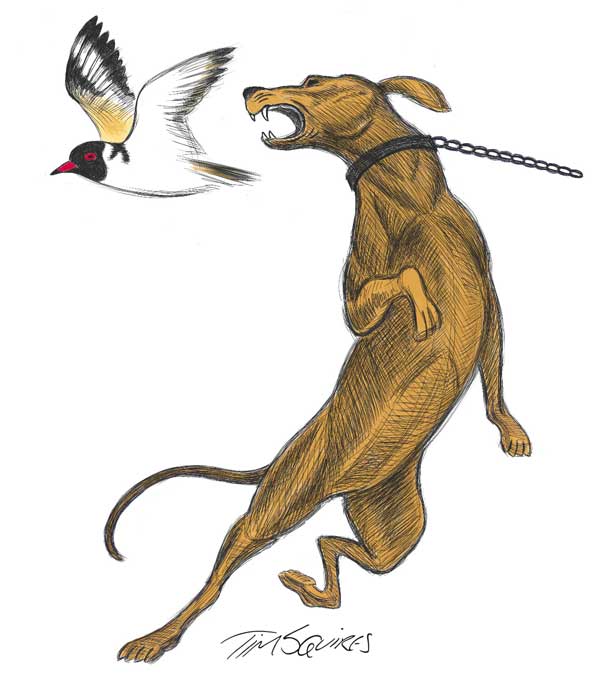

Such was the threat from human activity – and to a lesser degree predation by both native and feral birds and animals – that the hooded plover was now extinct along the beaches of Queensland and most of New South Wales, and in recent years had suffered staggering declines in numbers throughout the rest its range in South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania.

The threats posed to not only plovers but other beach birds like pied and sooty oystercatchers, red-capped plovers and, in the north of Australia, beach stone-curlews prompted BirdLife Australia to establish its special shorebird nesting project in 2006.

The project has been a great success so far and Ms Cullen reports that the tide is turning for the hooded plover on the mainland, and the little bird now looks set to make a comeback.

As she explained in her talk, one of the secrets of success has been mobilising the community in areas there the hooded plovers are threatened, not just to educate them about fragile plover breeding habitat but to encourage beach users to play their part in its protection.

This includes keeping dogs under control in beach-nesting areas and special education programs have been organised for dog owners on the beaches themselves. In Tasmania these early morning lectures are dubbed “a dog’s breakfast”.

Much money and man hours had been invested by BirdLife Australia in the project but what had made it special was the number of volunteers who had signed up to it over the years. In South Australia and Victoria there are more than 500 “Friends of the Hooded Plover” who not only monitor breeding birds, but erect fences around nesting sites and put up information signs.

Perhaps more importantly schools have also become involved, with children not only going out onto beaches to study plovers but building plover shelters – simple wooden roofed structures – that serve to protect chicks once they have left the nest.

While on BrunyIsland, Ms Cullen was planning to give a talk to children at BrunyIslandPrimary School about the importance of the island’s beach nesting birds.

The hooded plover has proven to be an ideal “flagship species” for the beach environment, not only because it is cute and easy to study but because the threats posed to it apply to creatures that live between sea and land. These include pollution and beach erosion, the menace of feral animals and weeds, and the intrusion of four-wheel-drive vehicles that can pose a danger to both bird, animal and human beach users.