The white goshawk flew in wide spirals, catching the thermals rising from the sun-drenched lowlands between sea and mountain.

The white goshawk flew in wide spirals, catching the thermals rising from the sun-drenched lowlands between sea and mountain.

The goshawk had come into view as I scanned the far-flung ocean looking for, of all things, whales.

The Mercury had reported in recent days that the whale season was underway with about 60 humpback and southern right whale sightings. It might have seemed a little fanciful to climb up to Sphinx Rock on the south-east side of Mt Wellington looking to the far horizons for whales but I thought I would give it a try anyway. On a previous clear, sunny afternoon I had spotted small fishing boats as far distant as Dunalley and through my binoculars seen the white foam of waves crashing against the two headlands that frame Primrose Sands a smidgeon closer, at a mere 30 kilometres.

Humpback and southern right whales were migrating from their feeding grounds in the Southern Ocean nearer Antarctica for breeding grounds along the Australian east coast. So why not look for them?

It was to be disappointment as far as whales go, of course. Trying to spot their form just under the water, a thin squirt of water breaking the surface, would have been the proverbial hunt for a needle in a haystack but it gave me reason to be on the mountain on such a fine winter’s day. Bedsides it gave me a focus other than birds which can become routine and predictable in winter, before the summer migrants arrive from the mainland.

The day was supposed to be about whales but suddenly all that changed with the sight of the white goshawk. By coincidence it was circling right over my usual stamping ground of the Waterworks Valley far down below me and it was a curious sensation to be looking down on a goshawk from the snow-covered Sphinx Rock. Usually I look up at them as they fly overhead on hunting sorties.

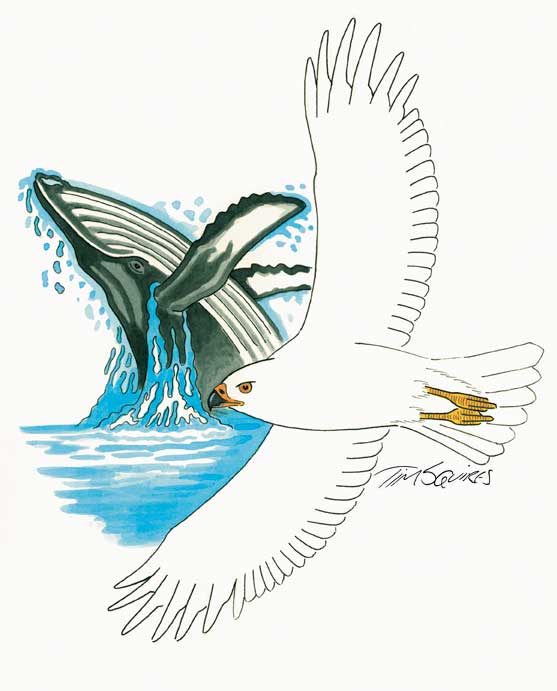

They really are the most beautiful of birds of prey, pure white with yellow legs and beak. The Tasmanian sub-species of the mainland grey goshawk (Accipiter novaehollandiae) is, as its local name suggests, a white form, or morph. The goshawks comprise a group of hawks which usually hunt by stealth and surprise, ambushing birds in canopy and thick scrub, and do not pounce from a great height like most other raptors, including the wedge-tailed eagle. I could only surmise this was a male goshawk mapping out its future breeding territory and announcing in powerful, soaring flight to rivals that this was his domain. It brought a sense of optimism I might find white goshawks breeding in the valley in spring.

When I first came to live in Hobart 12 years ago the white goshawk was a very rare bird having been hunted to near extinction locally from the time of white settlement. However, they have increased in number over the past decade as people show them more tolerance and respect and do not immediately reach for the shotgun when they see them perched on chicken coops.

Other threatened creatures increasing in number are the whales, and I look forward to the time when they are once again a common sight in Tasmanian waters, especially the Derwent estuary where they were so prolific once that they posed a threat to people in small boats crossing from shore to shore. Before whaling took its toll, the whales were also said to keep people awake at night with their slashing, breaching and peduncling activity in the harbour. It is heartening to report that whales are once again being sighted in the Derwent itself with a mother and calf being seen in the estuary in recent years.

Whales and white goshawks have a connection that goes beyond their threatened status in Tasmania, and even the curious possibly of seeing them both at the same time, from the snow-covered slopes of Mt Wellington. They are both connected to the delicate web of life that supports all living things and Hobart, and the world, would be poorer without them.